WOMEN WAR PHOTGRAPHERS

Musée de la Liberation of Paris, 8 March-31 December, 2022

LEE MILLER (1907-1977)

GERDA TARO (1910-1937)

CATHERINE LEROY (1944-2006)

CHRISTINE SPENGLER (B. 1945)

FRANÇOISE DEMULDER (1947-2008)

SUSAN MEISELAS (B. 1948)

CAROLYN COLE (B. 1961)

ANJA NIEDRINGHAUS (1965-2014)

WOMEN WAR PHOTGRAPHERS exhibit entrance BY Judith Bluysen

War photography has a short but rapidly evolving history. Although cameras were developed in the mid-19th century, photographic news coverage was sparse: cameras were bulky and exposures long, emulsions finicky to process. By 1927 Kodak had invented roll film, as German and Russian companies developed easily portable 35mm cameras. WWI birthed organized journalism, and by WWII it had become a vital component of the news industry, complete with photos. By the late 1920s a few determined women had begun to infiltrate the formerly all-male ranks of war photographers, receiving accreditation by hungry press services and armies. All of the seasoned photographers chosen for the exhibit WOMEN WAR PHOTGRAPHERS were highly recognized and awarded during their tenures as war chroniclers and beyond. It is interesting to reflect upon them as individual pioneers as well as a group, which is why I have included synopses of their individual bios.

Set in a leafy vest-pocket park, the inner vestibule of the Musée de la Liberation de Paris is luminous and airy. But once entering the enclosed space of this exhibition, all semblance of comfort and well-being explodes like a landmine.

The first room is hung with the earliest chronological photographs of the exhibit.

23 year old Jewish political activist Gerta Pohorylle fled Leipzig for Paris in 1933, where she met the Hungarian refugee photographer Endre Friedmann. Under the name GERDA TARO, she helped organize and promote his work; in return he taught her photography basics and together they created the personnage of an American photographer they baptized Robert Capa. In Barcelona to photograph the erupting Spanish Civil War in1936, the couple often published their photographs under the single entity of Robert Capa. Taro was killed July 26, 1937, at 27 years old, during her coverage of the Republican army retreat at the Battle of Brunette. Friedman kept the name Robert Capa, and later started the Magnum agency.

Taro’s photos chosen for this exhibition are both documentary military scenes and grimly humanitarian portraits. An orphan listlessly eats soup. In quasi-silhouette, a female soldier trains on a Barcelona beach, wearing pretty heeled shoes and kneeling on one knee, the other raised and bent, supporting an extended arm rigidly clasping a gun. Taro’s images of life on the perimeters of battlefields are more in line with much of the later work hung further in the exhibit, but this selection acts as a base to show the evolution of both photographic technology and vision. There is a tenseness of repressed emotion in her composition and and simplicity of technique: one feels the rapid heartbeat behind her lens.

LEE MILLER

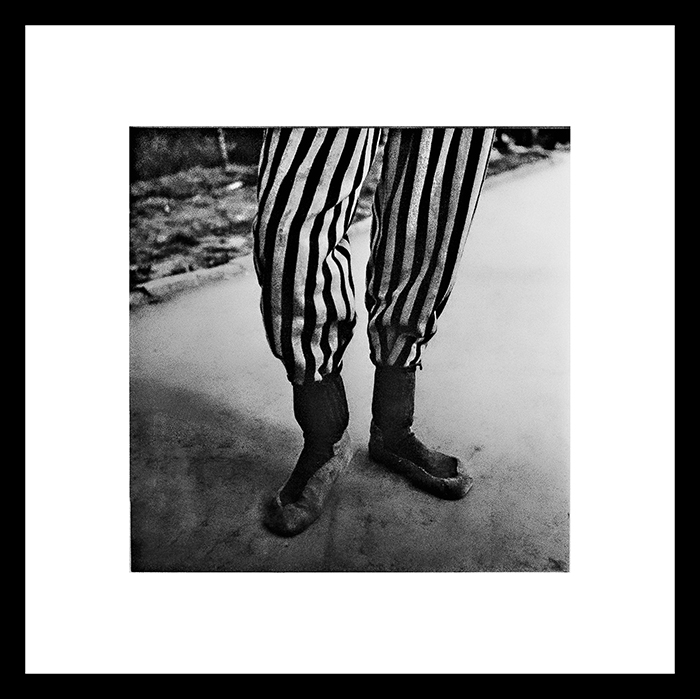

This space segues in to LEE MILLER’s. The trail of photographs is maze-like: it feels like crawling from one scene into the next. The first representation in the section is not by Lee Miller, but of Lee Miller, shot by David E. Scherman, the LIFE magazine correspondent with whom Miller often worked during this period. The pair were among the first journalists to converge upon Hitler’s abandoned Munich apartment: Scherman photographed Miller (who was, after all, a former fashion model) bathing in Hitler’s bathtub on April 30, 1945, the day Hitler committed suicide. The trail continues with Miller’s photos as a war correspondent for Conde Nast, documenting the liberation of Paris and the horrors of the Buchenwald and Dachau camps for Vogue Magazine. From the shaved head of a French woman who’d concerted with Germans, to the striped pajama-clad legs and feet of a camp inmate to the sprawling suicided body of the daughter of Leipzig’s mayor, Miller presents the dichotomy of a war photographer answering to a fashion magazine. To appreciate the diversity of her background helps understand the surreal qualities of her work: found symbolism replacing graphic content that in essence is more terrifying than realism.

In 1929, Miller had moved to Paris from her native New York to apprentice with Man Ray; subsequently she became his assistant, muse, lover and a vibrant part of the Surrealism movement. She left Ray and Paris in 1932 to return to New York to pursue commercial and portrait photography: her photojournalism career began in 1940’s London, documenting The Blitz for Vogue. She returned to London after the war and married the artist and art documentarian Roland Penrose: to combat PTSD and depression she turned to cooking and subsequently their home became a Mecca for the progressive artists whom she frequented before the war. Of the eight photojournalists represented here, Miller was the sole mother. Her son discovered the war photographs only after her death in 1977, and literally as well as figuratively, liberated them from the attic of history by establishing the Lee Miller Archive. Early in their careers, neither Taro nor Miller were always credited with their work: Taro’s photographs were sometimes ascribed to the then-fictitious Capa, and Miller’s art photographs to Man Ray.

CATHERINE LEROY

With no professional experience or training, the 22 year old Parisian CATHERINE LEROY arrived in Saigon in 1966 with her Leica M2 and began working with the Associated Press shortly afterwards. The first journalist to parachute into combat with US troops, she was later captured by the HUE during the TET offensive in 1968. Convincing them she was a French journalist whose mission was to document the bravery of the North Vietnamese soldiers, they permitted her to photograph the camp, then released her. Those photographs made the cover of LIFE magazine: some are exhibited here. Like Lee Miller, Leroy suffered from PTSD after the war. She moved to the US and covered the Woodstock festival and co-directed a documentary on Vietnam Vets before returning overseas to document international conflicts in 1975. In 1983 she settled in California to publish photobooks and to work on her Vietnam archives.

The 1967 stark black and white shot of Navy medic Vernon Wilke captures his anguish as, attempting to revive a wounded soldier in the field, he realizes his friend has died. 40 years later, in what would be her final story, Leroy was commissioned by Paris Match to photograph Wilke, which she did in soft warm color, as he leaned on a flag-festooned cane in his cramped Arizona bedroom. Her images still sting like a slap.

A bouquet of flowers provided by the artist in memoriam to the victims of the ongoing Ukraine War embellish French artist CHRISTINE SPENGLER’s niche in the maze. Spengler’s first photograph, shot with her brother’s Nikon while traveling with him in Chad in 1968 resulted in their arrest and imprisonment, and precipitated her career as a photojournalist. Focusing on the life of women and children during and post-war, she would adopt the dress and customs of her host-countries to attain intimacy with her subjects. Spengler was assigned to nearly every war zone—14, to be exact—by various publications or press agencies. Her final stint as a war photographer occurred during the Lebanese civil war, where in 1984 she was again captured and imprisoned as a Zionist spy. Released to return to Paris in extremis, she retired from war photography in 2003 and continued her work by adorning her black and white portraits with colored fabric, beads and broken glass, creating small alters as women have done throughout the ages as memorials to loved ones. Black and white photos of civilians amid the debris of war in Northern Ireland, Cambodia and Afghanistan surround the bouquet here: her camera captures their exuberance for life and portrays the resilience of human struggle.

Again a photographer with no formal training, the former French model FRANCOISE DEMULDER began photographing the Vietnam war in the 1970s, as the conflict became the first to be heavily played out in international news media. She had an extraordinary sense of timing, a facility for being at the right place at the right time, and for pressing the shutter at the auspicious moment. Her work here is not thematic, but more an an all-inclusive documentary portfolio of war. As with many of the field shots chosen for this exhibition, Demulder’s work is bare-bones action photography with little possibility of finesse in composition, depth of field or other “luxurious” considerations that exist in other genres of photography. Everything was manual as well and limited to 36 exposures per roll of film per camera before she had to stop and reload. Digital photography, a.k.a the ability to manipulate images, was quietly being developed by Kodak, but would not become accessible to photojournalists until towards the end of the first decade of the 21st century. Even 9/11 photographs were taken primarily with film, albeit with more sophisticated equipment (including video stills) than during the Vietnam conflict.

Demulder covered conflict in virtually all combat zones, garnering many awards, until her 2001 cancer surgery effectively put an end to her career.

Perhaps the widest-ranging photographer represented in the exhibit, the American educator, photographer, and filmmaker SUSAN MEISELAS, was heavily armed intellectually and technically by the time she began documenting the Nicaraguan revolution in the late 1970’s. At this point in this exhibition, the focus of the photography changes as technology becomes more sophisticated. The images selected for Meiselas’ small sampling are imbued with political and social consciousness and conscience. She was the first conflict photographer to extensively shoot in color, which brought attention to her work, therefore to the plight of Nicaragua and subsequently other countries battling dictatorship. Both storytelling and symbolic, she uses color like a painter, defining contrasts which serve to both emphasize and alleviate horror. While her early black and white series from New York and New England were necessarily analogue, she switched to digital once the technology became accessible and manageable. Each media has its own character and Meiselas uses both to perfection: her photographs themselves perhaps are not the desired end but the means of communication to reach it.

CAROLYN COLE

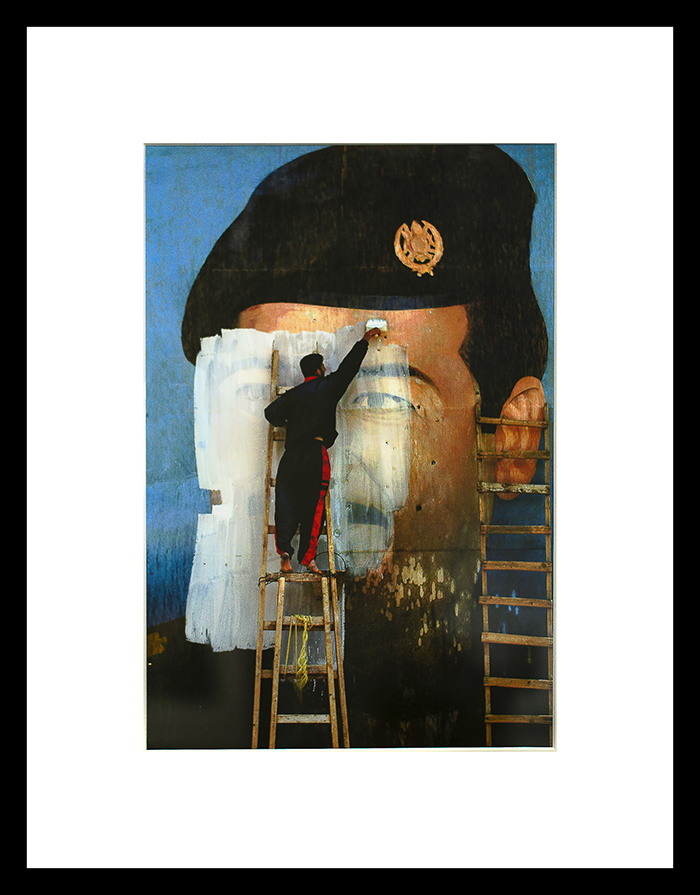

CAROLYN COLE was a staff photographer for The Los Angeles Times documenting conflict in Kosovo, Afghanistan, Irak, Haiti and Palestine. In 2003 she covered the siege of Monrovia in the emerging Liberian civil war, for which she won the 2004 Pulitzer Prize. Her images are modern magazine style, digital; replete with dramatic lighting, color, and composition. It is interesting to compare Cole’s and Anja Neidringhaus’ styles: the women are of the same generation, both career photojournalists who followed direct paths to the battlefields, yet their styles are completely different. While Cole’s photographs here communicate event and emotion, Neidringhaus’ images are event and emotion. This selection includes one of my favorite symbolic war photographs by Cole, that of an Iraqi man on a ladder whitewashing the mural portrait of a bullet-ridden Saddam Hussein.

The exhibition ends, as it has begun, with a German photographer. ANJA NEIDRINGHAUS’s photographs pulse with the quirky, staccato movements of war: laughing children play with a broken telephone as its wire trails amid the rubble of a devastated village in Gaza; the cartoonishly wide, wary eyes of both the American soldiers in, and the inhabitants of, an Iraqi home; and a Canadian soldier kicking a silhouetted chicken into the air as his unit flees a grenade attack. While she matured in the digital era, many of her images have the candid, unperfected aura of an unedited film photograph. Neidringhaus herself was shot dead, point-blank, in 2014 by a renegade Afghan policeman while traveling in a car with election workers, supposedly under protection of the Afghanistan Army and the Afghanistan Police.

As well as gaining access to families in political and religious conflict zones by the fact of their gender, female photographers were able to connect with the women without the various suspicions and constrictions male photographers raise simply by the fact of their own gender. Although this exhibition presents only 10 images by each of the photographers, women and children take center stage; despite the backdrop of war there is something tender about so many of them. Were their sensibilities heightened by the knowledge of a woman’s life, universally if only partially dictated by anatomy, and perhaps contrasting with their own personal lives? While many of these photojournalists maintained long-distance and long-term emotional relationships with partners, Lee Miller was the sole to bear and raise a child and to maintain a semblance of domesticity, although hardly a mainstream version. As Christine Spengler has said, it was impossible for their entourages to fully comprehend the realities of their lives. The subjects of these images are subtle bombs—vacant or penetrating eyes, hunched shoulders, defensive hands—in a sense a mute physical vocabulary, a dialect of compassion.

Admission to the museum, at Denfert-Rochereau and next to the Catacombs, is free. Admission to the special exhibit Women War Photographers is 6 or 8€. It is best to reserve online in advance.

This article about the exhibition WOMEN WAR PHOTGRAPHERS is by Judith Bluysen, a relapsed street photographer now shooting in Paris. Check out her website www.judithbluysen.com, or on Instagram @luluparee and her other articles https://fusac.fr/triple-exposure/

The photos for this article were taken during the author’s four visits to the exhibition.