Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson 79 rue des Archives, 75003

www.henricartierbresson.org @FondationHCB #weegee

REGARDS CROISES Henri Cartier-Bresson and Martine Franck and

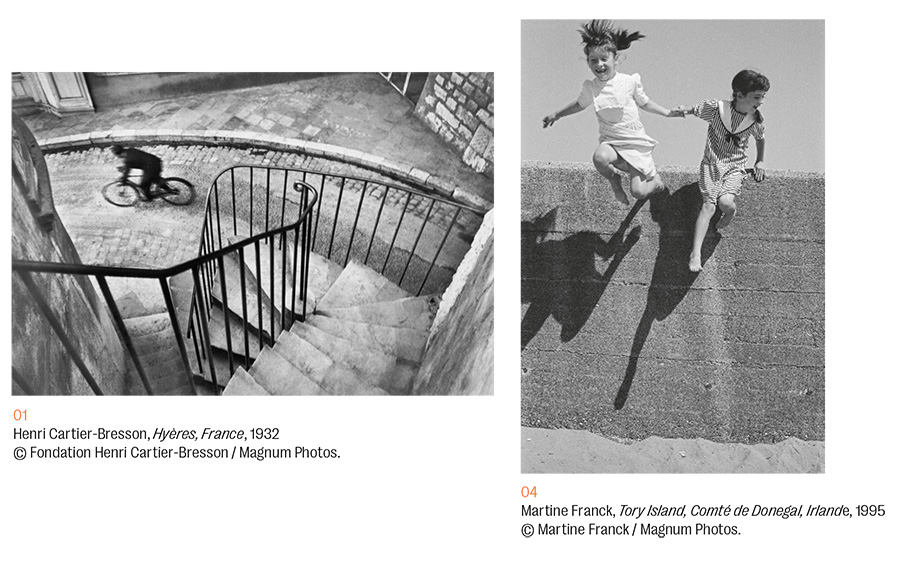

WEEGEE : AUTOPSY of the SPECTACLE Through May 19 2024 To celebrate its 20 years of existence, the Fondation HCB is sharing Regards Croisé, a small grouping of images created by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Martine Franck, highlighting the couple’s common themes. These gentle, lyrical images strongly contrast the “grab and gotcha” quality of Weegee’s work in the next room, and illustrate how two completely different styles of photography, in this case of the same general genre, can be so different yet each so iconic.

To celebrate its 20 years of existence, the Fondation HCB is sharing Regards Croisé, a small grouping of images created by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Martine Franck, highlighting the couple’s common themes. These gentle, lyrical images strongly contrast the “grab and gotcha” quality of Weegee’s work in the next room, and illustrate how two completely different styles of photography, in this case of the same general genre, can be so different yet each so iconic.

WEEGEE

AUTOPSIE DU SPECTACLE

Born into a Jewish family in Zloczow (then Austria-Hungary; now Zolochev, Ukraine) in 1899, the ten year-old Usher Fellig americanized his first name to Arthur upon immigrating to New York in 1909 with his family. Disinterested in school, he dropped out at fourteen and fell in love with the camera and its possibilities after an ambulatory tintype photographer made his portrait on the streets of Brooklyn. Cutting ties with his family at seventeen, Arthur lived on and off rough on Manhattan’s Lower East Side while scrounging various assistant jobs to learn the photo trade. Seven years later he was hired as a darkroom tech by Acme Newspictures where he honed his darkroom skills until 1935, when he left Acme to freelance as a news photographer. His base, at first, was Manhattan’s Centre Street police station: The second a teletype came in, Arthur shot out to cover the story, and, in 1938, he became the only New York City freelance newspaper photographer with a permit for a police-band shortwave radio. A night-bird of prey, he often beat the policeto the disaster or crime scene and so earned the name Weegee after the Ouija Board, for his apparent clairvoyance. (Another version of the transformation from Arthur to Weegee followed from his lab work as a ”squeegee boy”, drying prints for newspaper reproduction during his Acme days.) Whatever the truth, he developed his personal image the way he developed his photographic ones, with chutzpah, high definition and skill. Around 1940 he began stamping his photos “Weegee the Famous” and until the end of his life relentlessly exploited that fame.

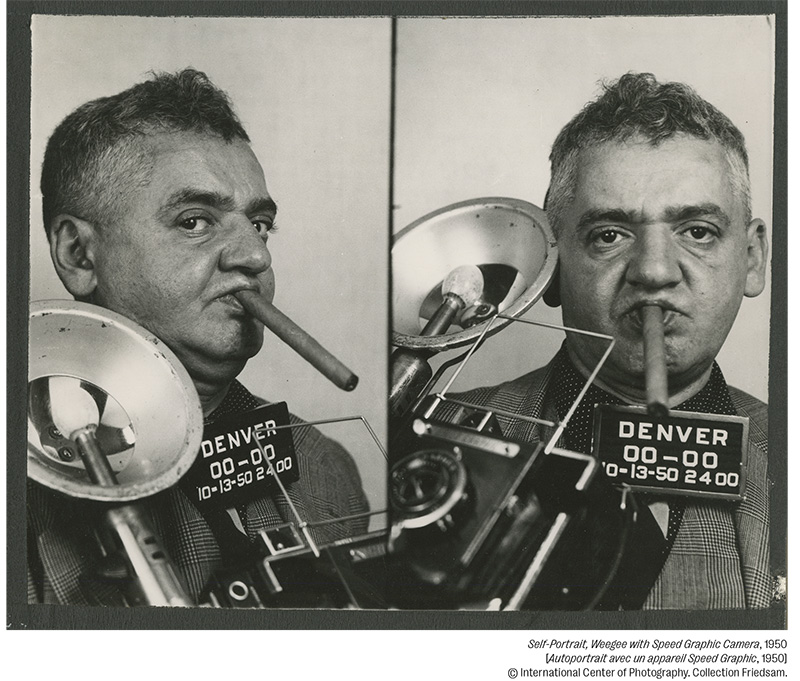

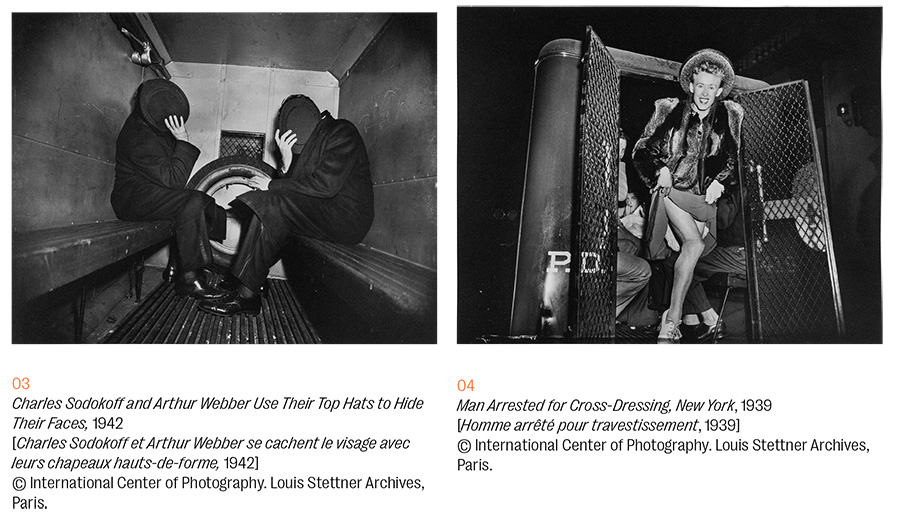

Clément Chéroux, director of the Fondation HCB, has catalogued the photos of Weegee’s sensationalist tabloid and hard-boiled documentary period in the first two of the three rooms dedicated to the exhibition. The first room, painted black and the most Noir in mood, leads with a couple of Weegee’s mugshot-style self-portraits: cigar clamped between meaty lips and his iconic Speed Graphic camera, flashgun attached, laying snug on his chest. Another shows him behind bars, again with the ever-present cigar and trusty camera. An invitation into his seedy world, the dark walls explode with disaster shots from 1935-46. Details define Weegee’s images: in a crumpled car shot, one empty shoe butts up against a wheel and a splayed hand dangles from a window: symbols of life extinguished. In another, a through-the-windshield shot, a young man tenderly holds a cigarette to the mouth of the wounded victim, whose face is reflected in the outer side mirror of the car. Did Weegee adjust the mirror to reflect the face, or did he simply adjust his camera to get the perfect angle? Across the room, transvestites camp for the camera while a variety of perps hide their faces behind hats, newspapers, hands or handkerchiefs as the police shove them into “Pie Wagons” for their trip to the precinct.

Clément Chéroux, director of the Fondation HCB, has catalogued the photos of Weegee’s sensationalist tabloid and hard-boiled documentary period in the first two of the three rooms dedicated to the exhibition. The first room, painted black and the most Noir in mood, leads with a couple of Weegee’s mugshot-style self-portraits: cigar clamped between meaty lips and his iconic Speed Graphic camera, flashgun attached, laying snug on his chest. Another shows him behind bars, again with the ever-present cigar and trusty camera. An invitation into his seedy world, the dark walls explode with disaster shots from 1935-46. Details define Weegee’s images: in a crumpled car shot, one empty shoe butts up against a wheel and a splayed hand dangles from a window: symbols of life extinguished. In another, a through-the-windshield shot, a young man tenderly holds a cigarette to the mouth of the wounded victim, whose face is reflected in the outer side mirror of the car. Did Weegee adjust the mirror to reflect the face, or did he simply adjust his camera to get the perfect angle? Across the room, transvestites camp for the camera while a variety of perps hide their faces behind hats, newspapers, hands or handkerchiefs as the police shove them into “Pie Wagons” for their trip to the precinct.

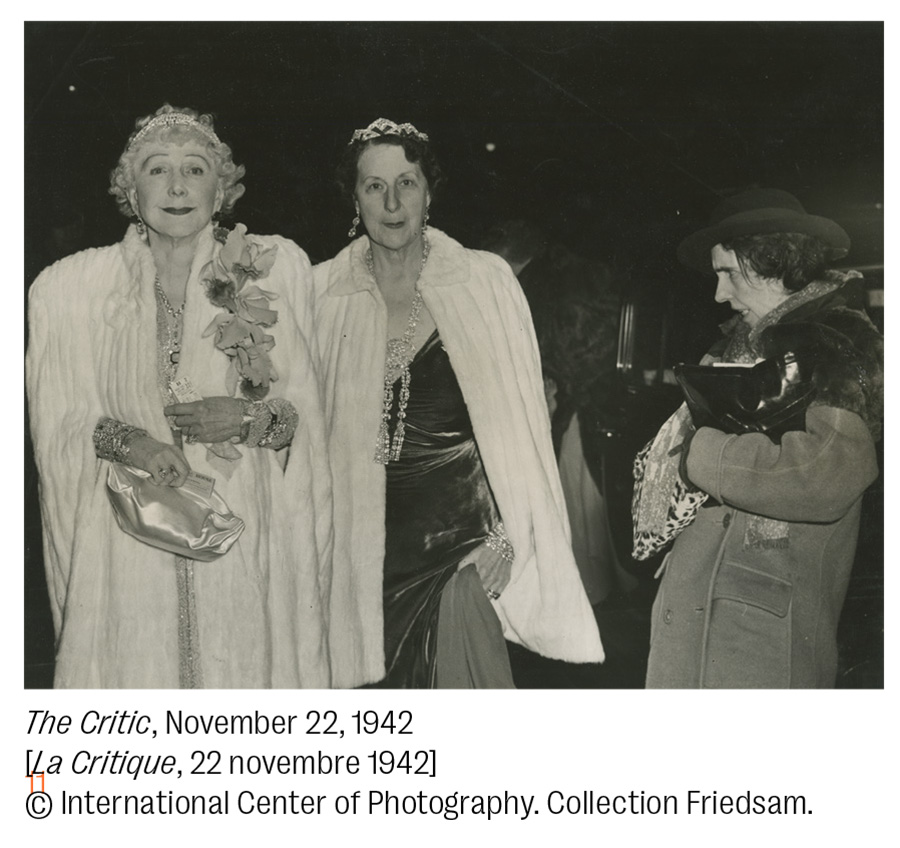

On the final black wall, quieter, internal human tragedies are documented: displaced families and homeless individuals sleep on the street. A Black mother and her young children stare out from behind a window smashed in a riot. A shivering ragpicker leads his horse through a blizzard, snowflakes blurring the image shot in slow motion. The white-walled middle segment documents the violent era and rise of the underworld as crime overtook American cities while American men fought the war raging in Europe. Here, bystanders rubberneck to snatch a better view of corpses sprawled in pools of blood while the police march handcuffed suspects in the perp walk : dramatic renditions of what Diane Arbus referred to as Weegee’s « wild dynamics”. His titles were art in themselves: the enraptured faces of teenaged girls witnessing the execution of a gambler on New York streets are frozen forever in “Their First Murder”. Distinctive angles and scale hurl the spectators as well as the exhibition viewers into the heart of the drama. In another shot from 1939 he originally titled “Roast”, Weegee captured the agonized faces of a mother and daughter witnessing their home burn with remaining family members still inside. Editorial refused to run the photo with that title, so he shrugged and changed the slug to “I Cried When I Took This Picture”, exemplifying what we come to discover about him in this beautifully and thoughtfully curated exhibit: he’s not just a grinning sensationalist goon with a big-ass camera, but a social documentary photographer with the eye and mind of a satirical artist. In 1940 Weegee became one of the founding photographers of PM, a new liberal/leftist tabloid devoted to telling stories with photographs. As his brand became ubiquitous he fed his reputation by embellishing programmed events and shooting them as news: “The Critic” is the most famous of these.

On opening night of the Metropolitan Opera House’s sixtieth season, he allegedly coerced, by alcohol and his special brand of cigar-chomping charm, a female fellow habitué of Sammy’s Bowery Follies Bar to accompany him to the event, and plopped her smack into the entrance photo-op of two of New York’s most famous high society matrons. The stark contrast between the flash-enhanced ermine-coated glittering socialites and the shabby, confused, drunken woman in the lower corner of the photograph crowned his career as a photojournalist. Never admitting that the photo had been staged, he later proclaimed it a masterpiece and personal favorite of his entire oeuvre.

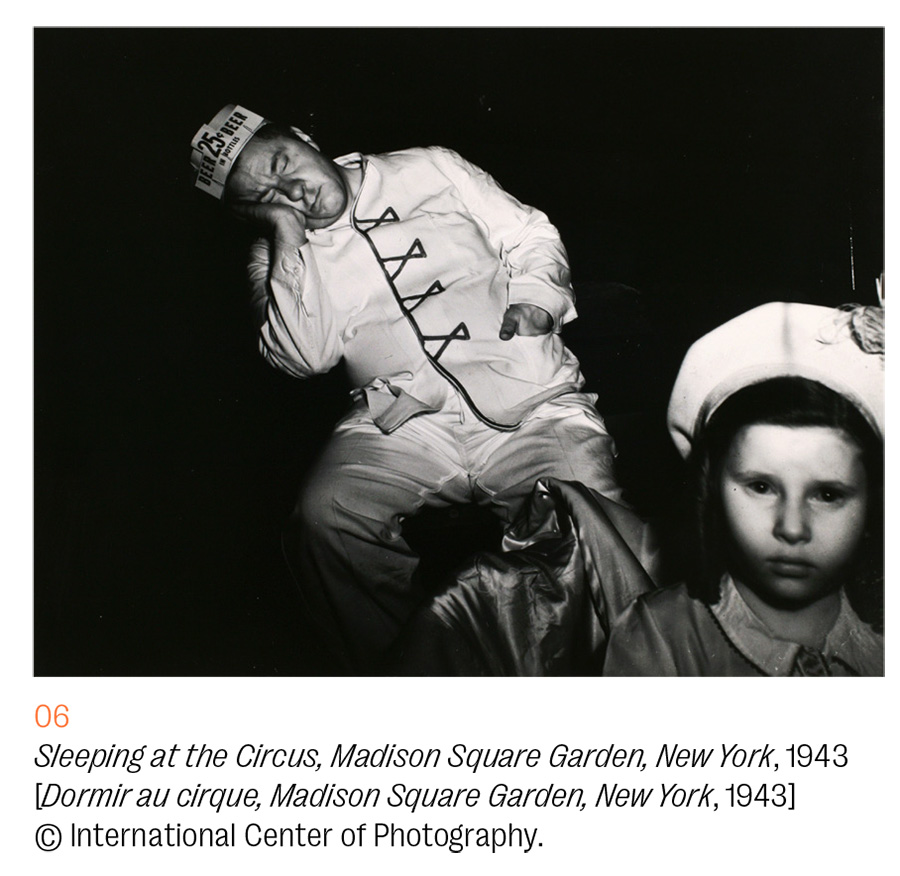

A series of candid shots from 1945 is included in this space. Annoyed by people composing their expressions when spotting his camera, Weegee procured some infrared film and, in darkened theaters, proceeded to photograph unaware subjects: mesmerized bleary-eyed children losing themselves in the film, or teenage couples passionately losing themselves in each other. A circus peanut vendor sleeps in an empty row of seats. While his subjects were indeed unaware of being photographed, the experiment lent a decidedly un-Weegee-like effect. In the dark, emotions produced by the entertainment remain within the subjects rather than stamped on their faces. Flat grays, low contrast, and relaxed postures birth tepid photographs, sort of like no one being home when he knocked. Another white wall displays image after image of groups of diverse pedestrian faces gawking as a small unseen plane crashed into the Empire State Building. The final three images are close-ups of the back of heads and hands waving excitedly in the air, and contain more emotion than the expectant but blank faces on the wall before them.

Ten years is a long time to cover murder and mayhem 24/7. In 1943 five of Weegee’s photos were acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, which he hoped would launch his career as a “serious” photographer. While he was not taken very seriously by much of the art-world, he remained a popular figure based on reputation, and “Weegee the Famous” published his first photo book, Naked City, in 1945. He sold the title rights to Hollywood producer Mark Hellinger, and moved to Hollywood in 1947, when Hellinger made the Noir-ish film Naked City. The story of the murder of a young model, in which Weegee both consulted and played a bit part, it was directed by Jules Dassin, and released in 1948, after which it became a classic late night TV series lasting four seasons. Also in 1948 Weegee’s MOMA photos were chosen by Edward Steichen to be included in the MOMA exhibition 50 Photographs by 50 Photographers, and at that point he completely dropped newsprint, abandoning his tabloid shockers for a more artistic form of photo commentary.

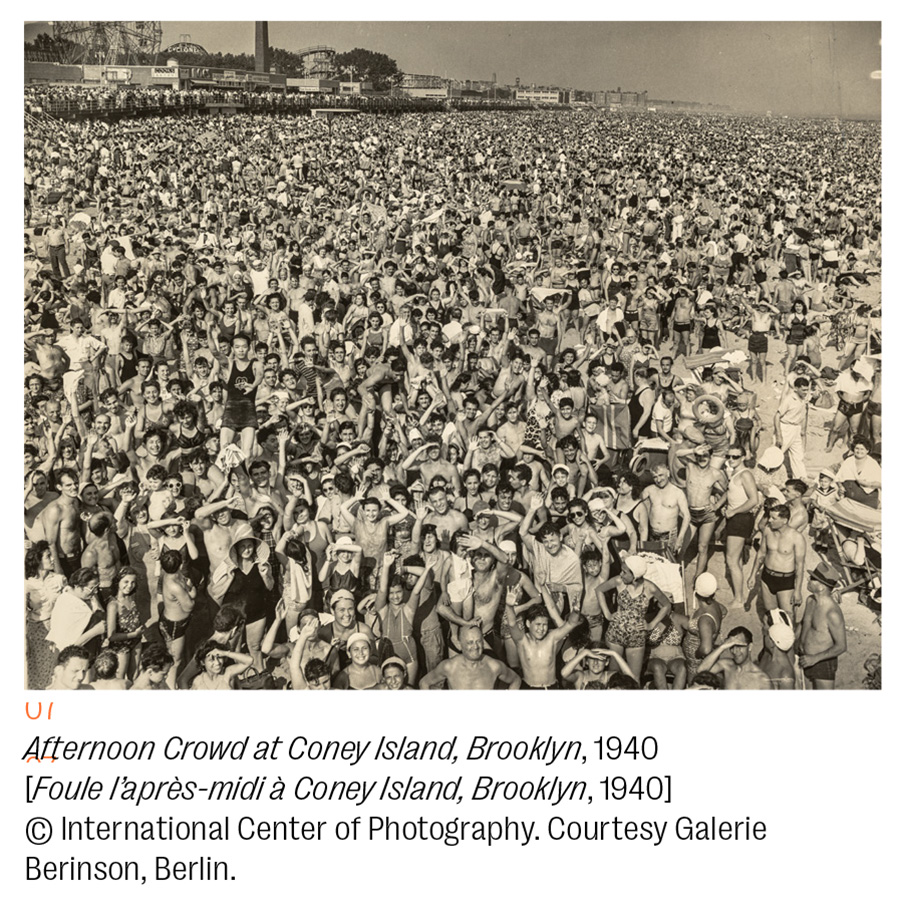

Weegee’s personal style of social documentary and his caricatures are presented in the final, Silver room. Examples of his earlier personal work are included as well: the panoramic Coney Island crowd shots he reportedly loved shooting, the Times Square War Bond Rallies, as well as his Lower East Side neighbors: Bowery vaudeville actors and actresses, immigrants, merchants, and clowns in full dress and makeup but not clowning. These photographs feel more personal and documentary than his newspaper work, yet have the unmistakable if softer Weegee in-ya-face trademark feel.

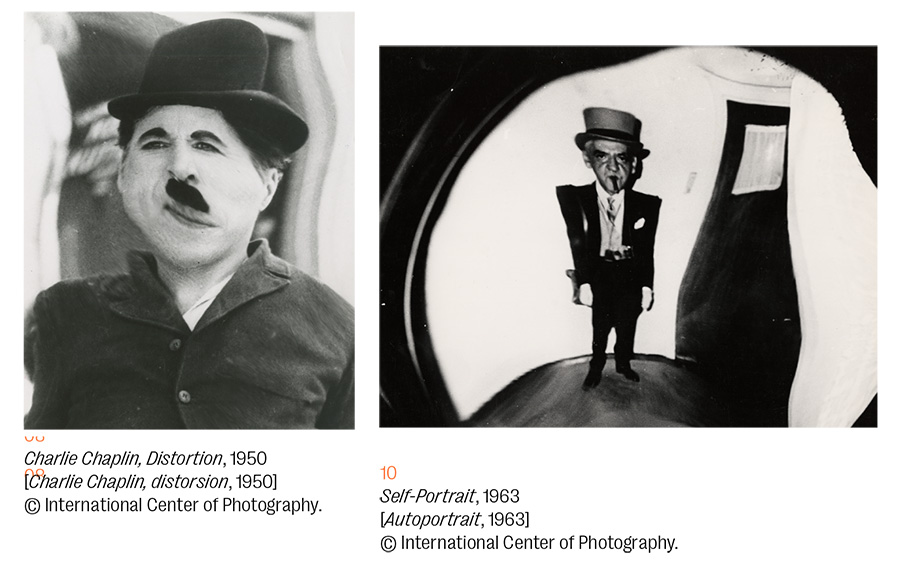

Working seriously on his photographic distortion portraits while in Hollywood, Weegee continued to diffuse them in various press vehicles until his death from a brain tumor in NY in December 1968. Rather than capturing reality, he used deliberate distortion to define and editorialize his subjects. He concocted filters of curved and textured transparent materials that he placed between the enlarger lens and a sheet of photosensitive paper, and in some, partially melted negatives or switched a kaleidoscope for the lens. From a squeaky-voiced vulture-like presence hovering around carnage sites, Weegee transformed himself into a sort of society muse, shooting a new milieu in his classic style, never losing his eye for ironic detail. Returning to New York in 1952, he used his notoriety to publish photographic how-to manuals and photo books, while continuing to sell his caricatures to mainstream magazines. The portrait gallery included in the Silver Room contains sardonic images of Mao, jaw tilted upwards showing hugely distorted jackass teeth; Jackie Kennedy sporting a bulbous bouffant forehead, and Marilyn’s puckered lips stretched so far as to appear missile-like, foreshortened and hard. On an opposite wall, a triptych of Charlie Chaplin in various metamorphoses and Charles de Gaulle with an extra-long chin melting into his neck are hung, as well as a few self-portraits.

A final wall is crammed with framed newspapers and magazines of the day featuring examples of Weegee’s special prowess of histortion and caricature.

A final wall is crammed with framed newspapers and magazines of the day featuring examples of Weegee’s special prowess of histortion and caricature.

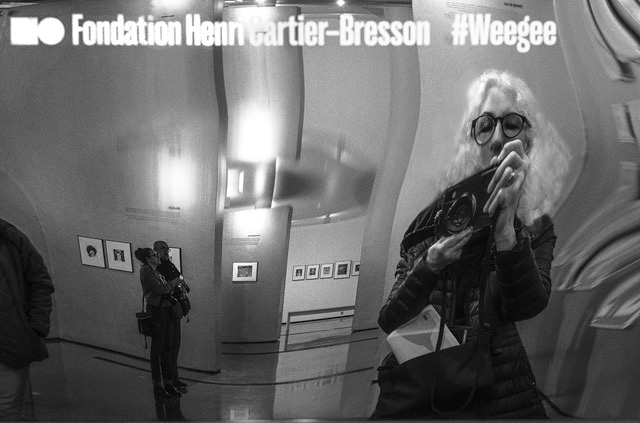

To the right of the gallery exit door, a large mylar distortion mirror allows viewers to self-Weegee:

Look Mom I’ve Been WeeGee’d by Judith Bluysen https://www.instagram.com/luluparee/

And, as the viewing public was reminded, after every segment of the television series Naked City:

« There are eight million stories in the Naked City. This has been one of them.”

This article about the exhibition WeeGee: AUTOPSY OF THE SPECTACLE is by Judith Bluysen, a relapsed street photographer now shooting in Paris. Check out her website www.judithbluysen.com, or on Instagram @luluparee and her other articles on FUSAC: