They met in Paris, here’s how YOU can meet your âme-soeur or just good friends in Paris https://fusac.fr/how-to-meet-people-in-paris/

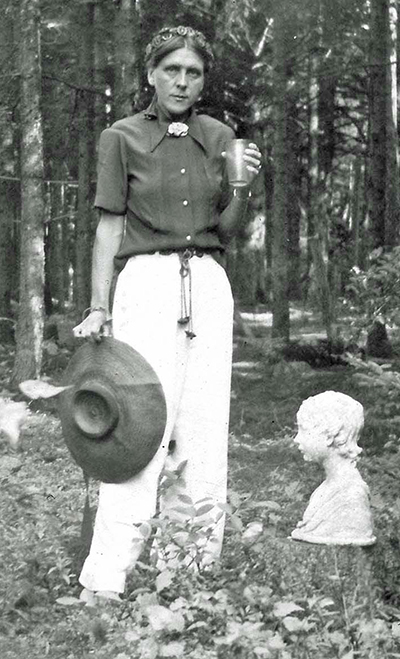

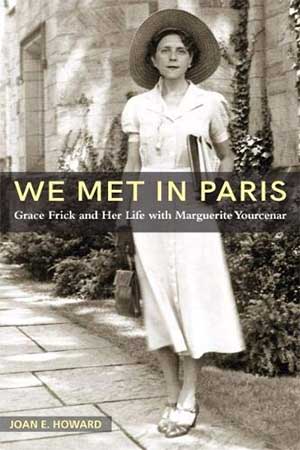

We Met in Paris is the double biography of Grace Frick, the companion who created the world in which one of the best French authors could write, and of Marguerite Yourcenar the author of The Abyss and Memoirs of Hadrian (Selected as one of the « 15 books to better help you understand the Hexagon » in our 2018 LOOFE). Yourcenar was also the very first woman inducted into the Academie Française in 1981. Joan E. Howard, the biographer, had the luck to not only meet Marguerite Yourcenar in the early 1980s but to become a friend and spend several summers with “Madame” before she died. In 2000, Howard, given her personal contact with Yourcenar, became the director of Petite Plaisance, Margueritte Yourcenar’s home on Mount Desert Island on the coast of Maine. The home was labelled a “Maison des Illustres” in 2014. Ms Howard was also selected to translate a French biography of Marguerite Yourcenar to English. The biography was criticized for its portrayal of Grace Frick by those who had known them both. Ms. Howard today presents us a counterpoint in We Met in Paris.

The early chapters give a detailed account of Frick’s family history and provide a captivating insight into the world of American higher education in the 1920’s. A born teacher, Grace Frick very much valued creativity. We also see the generosity that later helped her to create the environment in which Yourcenar was able to flourish as a writer. Grace Frick was much more than translator/editor/literary assistant or whatever title she gave herself. She was the driving force behind Yourcenar’s career. Céline Samson

There are multiple facets and ways to enjoy We Met in Paris. In addition to the details of Grace Frick’s career and relationship with Margueritte Yourcenar it shows an overview of the development of the history of education for women in the USA, it also talks about female relationships. There are also many references to travel, translation, teaching. We are privy to the trials and tribulations of a French expat in the United States in the mid twentieth century as Yourcenar tries to find a way to stay in the United States during war time, to earn her living, in both lucrative and meaningful ways, with her primary skill – initially- being her mastery of the French language. Marguerite Yourcenar is quoted as advising a homesick young Frenchman that to feel at home in America one must create, “as Grace and I have, a domain, however small it may be, governed by fantasy or one’s personal wishes.” As an expat the reader can appreciate a kinship with Madame Yourcenar that we never imagined could exist.

The reader encounters two worldly and creative women who love music, literature, nature, animals, history, travel, Roman ruins and each other. The book spans the 1930s to 1970s, the era where overseas trips to Europe lasted 6-24 months, travel was by ship and communication by letter. We Met in Paris is precisely and meticulously researched with hundreds of first person interviews and documents such as grades, passport stamps and ship manifests plus important historical context such as World War II, McCarthyism and racial protests. Ms. Howard’s writing is also not devoid of humor and very engaging to read.

“In this remarkable and essential first biography of Grace Frick, Joan E Howard paints the figure of the 20th century woman eager to promote women’s education and and to defend civil rights; a woman passionate about literature who became the indefatigable translator of the works of her lover, the French writer Margueritte Yourcenar. Against the clichés spread by many of Yourcenar’s biographers, Howard does justice to the relationship between the two women, to the life they chose to build together, and gives a deeper understanding of their in twined literary careers.” – Béatrice Mousli, University of Southern California, author of Susan Sontag

To whet your whistle for We Met in Paris, a most captivating book, we have chosen two excerpts. The first comes from Chapter 19 which covers the period 1952-1954 when « Memoirs of Hadrian » has just come off the press. Grace and Margueritte headed to Paris for the event and the book is highly appreciated by the cream of literary Paris. The second except, from the same chapter, but written in 1965, is a letter from Grace Frick to Nancy Kimball Ho with some important reflections on « mixed » marriages. It was advice to a young bride that still resonates today.

THE WEEKS AFTER MÉMOIRES D’HADRIEN came out brought a whirlwind of book signings, media interviews, luncheons, dinners, and parties—one of them a Christmas Eve eggnog gathering at the Hôtel Saint-James that lasted until midnight. Marguerite Yourcenar’s success and her sudden celebrity surpassed all expectations. Old friends and new, attracted by the book, came pouring in. Among the former were Grace Frick’s Wellesley classmate Florence Codman, who came to Paris shortly after Hadrian was released and helped Yourcenar connect with the American publisher Farrar, Straus and Young; Jean Cocteau, with whom the couple dined between Christmas and New Year’s; Yourcenar’s first publisher, René Hilsum; and the French author Roger Caillois, whose chair at the Académie française Marguerite Yourcenar would one day occupy. Among the most notable new friends were the Argentine writer and publisher Victoria Ocampo and the Chilean-born marquis and ballet impresario George de Cuevas. Ocampo’s literary magazine Sur counted Jorge Luis Borges and José Ortega y Gasset among the members of its editorial committee and published numerous renowned French authors on its pages. A staunch antifascist during the war, Ocampo was imprisoned in the 1950s by the dictatorship of Juan Perón. Marguerite Yourcenar would join Albert Camus, François Mauriac, Ernest Hemingway, and other writers in speaking out against her detention. The Marquis de Cuevas, as Grace noted in the daybook, invited Yourcenar to dine with him on January 19, 1952, “without knowing her, but adoring the Hadrien.” Marguerite and Grace would see a lot of the marquis in the weeks to follow.

With Yourcenar a sought-after commodity, social life was very much the order of the day. The British writer and socialite Nancy Mitford provides a glimpse of those hectic weeks from an unusual angle. Angel Gurria-Quintana calls Mitford “a Francophile who never quite took to the French literary establishment,” viewing it as not entirely reputable. As if to exemplify its shadiness, Gurria-Quintana quotes from a letter Mitford wrote on February 1, 1952: “I went to a terrible dinner to meet Mlle Yourcenar. All but me were drugged to the eyes & clearly orgies were about to take place—prim & English, I fled.” Yourcenar and Frick dined with de Cuevas on January 30, along with Princess Bibesco and her attaché. It’s hard to imagine them “drugged to the eyes,” though the wine no doubt flowed freely at the marquis’s table. If there was an orgy, it goes unmentioned in the daybook, as does Mitford.

The pace of life slowed down somewhat after Frick and Yourcenar left Paris, heading for Rome, on February 10. En route they stopped in Pau, to settle Christine de Crayencour’s estate, and then on the French Riviera. In Cannes they discovered the pleasures of traveling by horse-drawn carriage, a mode of transportation that would figure prominently over the upcoming weeks. Yourcenar once told a friend that these leisurely rides were a “particular delight” for Grace, the equestrian, though they surely held appeal for Marguerite, whose bedroom at Petite Plaisance is exclusively decorated with artistic images of horses. The couple’s first carrozza trip took them to de Cuevas’s villa, Les Délices, on the avenue d’Antibes. They would have luncheon at Les Délices several times over the course of their week in Cannes. Mémoires d’Hadrien had inspired the marquis to conceive a ballet about Antinoüs.

In Italy the couple spent two months following in the footsteps of their younger selves. They reached Rome in late February, staying at La Residenza, where they had been new lovers in 1937. On Sunday, March 2, just as they had done upon arriving in Sicily in 1937, the women attended a performance of marionettes.

Hadrian’s success had prompted the reissue of Yourcenar’s previous works, the first one of which was Alexis. Both Frick and Yourcenar, each with her own copy of the text, pored over the original edition, carefully checking and correcting it. When Alexis was reissued in the spring of 1952, Yourcenar would inscribe a copy “to Grace, with gratitude and tenderness,” adding in Greek, “You have made me forget my cares.”

Before departing for Spain in late April, the two women made several trips to the Villa Adriana. Spain had been off-limits to Yourcenar and Frick in 1937 because of the civil war. This time they had their sights set on Seville. Departing from Genoa, they stopped in Gibraltar, Algeciras, and Cadiz, one of Europe’s oldest continuously occupied cities. Seville was near the ancient site of Italica, Trajan and Hadrian’s birthplace, and its museums brimmed with artifacts from that era. It was in Seville that mention is first made in the daybook of Frick translating Hadrian. After visiting the Museo de Bellas Artes and a carriage ride back to the bottega for lunch, Grace wrote, “Translated the rest of afternoon and till eleven at night, when we went by taxi to Cabaret (Bar Citroën) to hear Spanish singing.” Three days later, with Yourcenar keeping the daybook, they translated all day long.

In “Andalusia, or the Hesperides” Yourcenar would later speak of how intimately linked for her and Frick were the human and the historical dimensions of their travels in Spain:

Let us list its delights for us: Granada was beautiful, but that nightingale who sang every night, its dark throat swollen with song, taught us as much about Arab poetry as the inscriptions in the Ahlambra. Beside the ocean at Cádiz, among buried stones which may be those of the temple of Hercules of Gades, that young boy with his brown legs, standing up to his thighs in water which was as pale blue as his washed-out rags, concentrating only on the rewards and disappointments of his fishing, moved us as much as the ancient statue we found at the water’s edge. That aged, half-blind nun who showed us the paintings in the Hospital de la Caridad without seeing them herself takes her place in our memory beside the painted figures.

On May 17 a telegram arrived announcing that Mémoires d’Hadrien had won the Prix Femina-Vacaresco. Yourcenar was expected for the June 4 ceremony. Back in Paris, she and Frick went with Natalie Barney on May 30 to the opening of Virgil Thomson’s opera based on Gertrude Stein’s Four Saints in Three Acts. The couple were delighted to run into their old friend Chick Austin there and would see him several times before returning to America in August.

Yourcenar, who never liked command performances, was informed in a letter from the perpetual secretary of the Femina committee that she was not invited to the luncheon at the Ritz which the “Femina ladies” would attend before handing over the prize. Frick’s opinion of that arrangement can be deduced from her comment in that day’s agenda: “Prix Femina Committee to give Vacaresco Award, at the Ritz. M.Y. to come at 2:15, like a sheep.”

Yourcenar herself was often of two minds regarding literary prizes, though she knew that they performed a crucial role in bringing attention, and new readers, to her work. Moreover, June was not without its finer moments. On June 7, supposedly Marguerite’s birthday, the couple took a dinner cruise on the Seine, viewing an illuminated Paris beneath a “very beautiful” full moon. On June 19 George de Cuevas took Yourcenar to meet Colette at the Palais Royal, not far from the Hôtel Saint-James. We have only one fragment of conversation from that meeting, which Yourcenar herself reported to the Belgian Royal Academy in 1971. Colette, a writer so different from herself, was one of several “invisible presences” whom Yourcenar conjured, along with her mother, Fernande, and Jean Cocteau, to join the academy audience that day: “I saw Colette only once, twenty years ago. Already sickly and reclining on her chaise longue, she bestowed on me the general’s embrace of a modest lieutenant and paid me the most succinct of tributes (at least I hope I can label it a tribute): ‘Memoirs of Hadrian? Goddamn!’ ”

In early 1965 Grace Frick reached out to share her experience as part of a “mixed marriage” with her young neighbor Nancy Kimball Ho. Nancy lived just a few houses up the street on South Shore Road. Nancy had recently married an Asian man, Robert Ho, despite the adamant objections of her gravely ill father. Grace knew the Kimballs, and she knew Northeast Harbor. She believed she could help the young bride:

I understand from your good friends, the Coffins, that it has been hard for your father to adjust to your decision about this marriage, but I have not talked to your parents about it, knowing how upset the winter has been for them. I only wanted some word to go to you from this town over the holidays (perhaps you have already heard from friends here?), with a Northeast Harbor postmark, that said plainly that the writer did not view with alarm a marriage with a foreigner! I know nothing, of course, of the circumstances in which you married, but if New England is to keep its tradition of strength and resourcefulness it will have to receive new blood from time to time, as it did in the days of its seafaring captains and shipbuilders.

. . . This particular Maine coast was settled by relatively recent immigrants, of highly mixed origins, however good the stock proved to be, as [the historian] Sam Morison is fond of pointing out. And our civilization, if one can call it that in this whole country, is fairly young compared with that of the Orient. It is high time that we learn to combine what is good in our various cultures, and stop trying to perpetuate the mere differences.

New England, and particularly Mt. Desert, both summer and winter, has much to learn on this score, and perhaps you and Robert can make a real contribution in that direction. Every such marriage is made for highly individual reasons, but the first reactions to it, on the part of others, are apt to be wearisomely the same, so I wanted you to know that if you think that you have made a wise choice we hope that you will not be deterred by mere prejudice, and that you will be able to prove by your two lives that no such prejudice should ever have existed.

One does not break down thought habits, and non-thinking habits, of a life-time very easily, and doubtless you will encounter points of view in yourself which you have never clearly recognized as partial, prejudiced, or provincial. (I write, you see, as one who has long had the good fortune to see myself, my country, and my Anglo-Saxon origin through Gallic eyes, and to find that even after thirty years, I am still unable to account for certain tastes and opinions when asked point blank why I think I am justified in holding them!) You will come to know and judge your own land better for having help from the outside, like light from another planet! The process is sometimes painful, as you may already have discovered; but the main point is to learn to evaluate correctly what is substance and what is merely external (a vestige of something real enough in the past perhaps, but no longer pertinent or true).

Good wishes to you both, Grace Frick

This handwritten letter resonates profoundly with the challenges that Frick herself faced in becoming involved with Yourcenar, from its reference to the wearisomely same first reactions of others to the idea of living as a couple in such a way as to show that “no such prejudice should ever have existed.” It also acknowledges the challenges inherent to nontraditional or intercultural pairings as well as the salutary effort of self-examination to which they inevitably give rise. Even thirty years into her own “marriage,” Grace still saw that effort as a stroke of good fortune.

Order We Met in Paris on Amazon – paperback copy coming out 31 March – ebook available on Amazon US